Disclosure: These numbers have been presented in earlier forms at a panel at The Business, organised by Sam Riviere at the University of Edinburgh, and at Special Relationships: Poetry Across the Atlantic Since 2000, a symposium at the University of Oxford. All my thanks to Muireann Crowley for being a sounding board and strengthening this article’s argumentative structure; to the Scottish Poetry Library for keeping a well-stocked and accessible magazine archive; to all folks at the symposium for their questions and inquiries about the project.

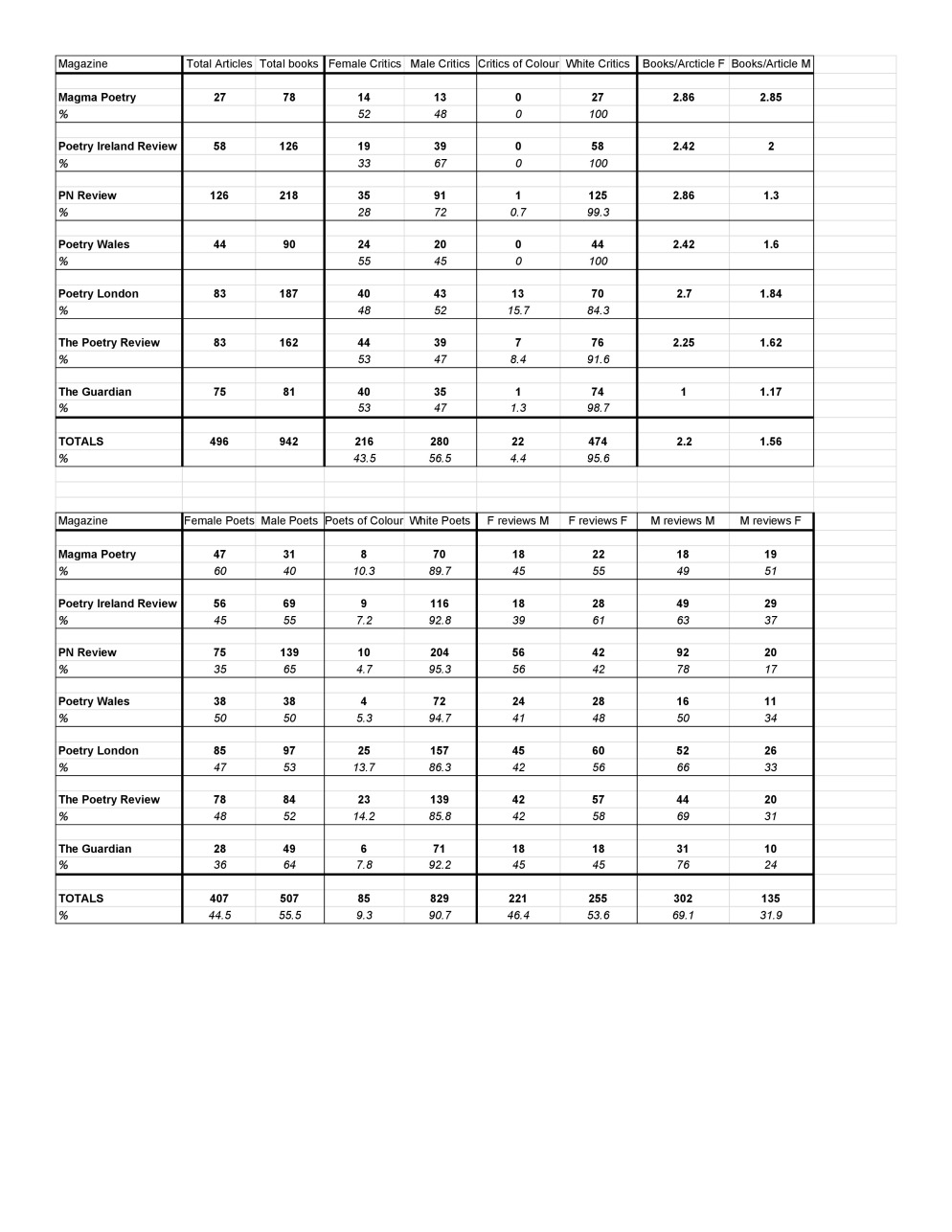

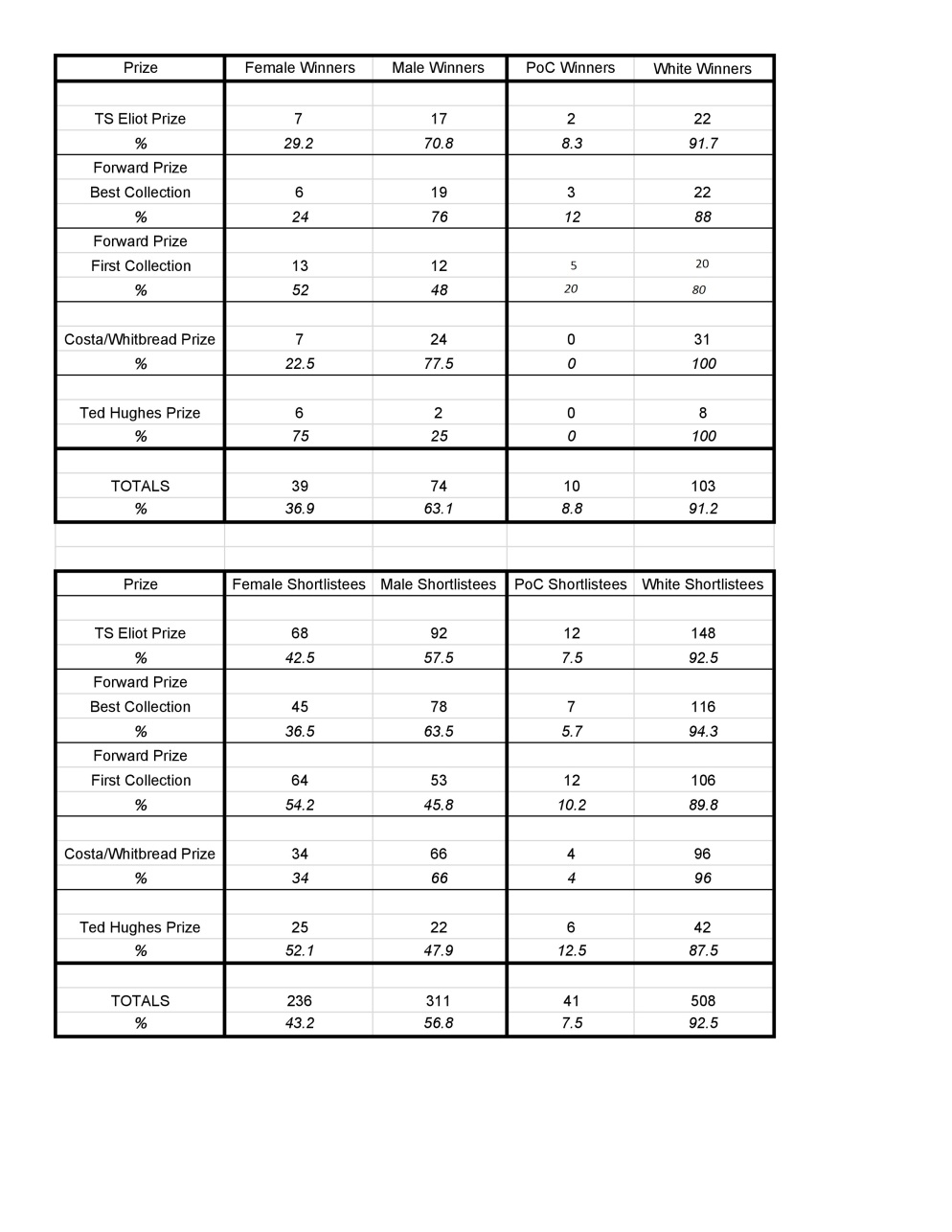

The figures cover a period of 24 months from April/Spring 2015 to May 2017 – while they do not account for every poetry review published in these islands, it certainly accounts for some of the most prestigious publishers of criticism, over a substantial period of time. Please note that these numbers do not refer to interviews, features, reports or other prose works, only what each magazine refers to in its contents as reviews.

Edit: Regarding the Forward Prize for Best First Collection, I somehow overlooked Tishani Doshi and Daljit Nagra’s wins in 2006 & 2007 respectively. Sincere apologies to Tishani, Daljit and the Forwards for this error.

Click the images below for a larger version of the data collected for this article.

Data:

Essay: In the past few years, it seems like poetry culture in these islands has been making small positive steps towards greater inclusivity – women of colour won both Forward Prizes in 2015 and 2016, and the 2014 anthology of new black, Asian and minority ethnic poets, Ten: The New Wave, edited by Karen McCarthy Woolf, has proven a successful springboard for its poets, eight out of ten of whom have since published pamphlets or full collections. Literary journals and magazines have been less encouraging, if not downright antagonistic: Vahni Capildeo’s Forward Prize win was met with evidence-free claims of nepotism from Private Eye; TS Eliot Prize winner Sarah Howe was described by her Sunday Times interviewer as having ‘sixth-formy emphasis on her own intelligence’ before admitting he just didn’t understand the work; Oxford professor emeritus Craig Raine accused Claudia Rankine of ‘moral narcissism’ in her Forward Prize-winning book Citizen. Prize culture, at least in the past few years, seems somewhat more advanced in its discourse around work by poets of colour than the critical culture surrounding it.

From this starting point I wanted to investigate a possible disconnect between prize culture and literary review culture. While not all critical responses have been as hostile as those above, the most common response to work by poets of colour has been total silence.

I decided to conduct a basic survey of poetry criticism and prize culture. I identified seven magazines which most regularly print a substantial amount of poetry criticism, and started counting. The questions this research asks are simple: whose poetry is reviewed? and who is commissioned to review it? Those publications are: The Guardian, The Poetry Review, Poetry London, PN Review, Poetry Wales, Poetry Ireland Review and Magma. In each case I studied issues dating from April/Spring 2015 to the present day (May 29 2017).

There are obvious limitations on the data I have collected. These figures cover gender and racial/ethnic distribution. They do not cover other intersections of cultural exclusion like class, disability, access to education, or sexuality, and on race and gender they are unsophisticated. For instance, unless a poet or critic identified as non-binary gender in their bio, I could not collect that data.

The racial categories I have used are also unsatisfactorily binary: ‘white’ and ‘people of colour’. The decision to assign a particular category to an individual was based on available biographical information and the individual’s self-description. This reductive binary is also a matter of expedience: so few poets and critics of colour are published that by grouping them together the overwhelming whiteness of British and Irish poetry criticism becomes impossible to ignore.

Finally, one additional side note on terminology: ‘articles’ refers to a full piece by a critic, which may criticise more than one book. “Critic Z reviews Poet A, Poet B and Poet C”, for example, is one article by one critic covering three books by three poets. You may also notice that in the final columns some of the percentages don’t add up to a hundred – this was when anthologies were being reviewed.

Let’s start by looking at race. The 2011 census reported that people self-identifying as black, Asian or minority ethnicity comprised 12.9% of the total UK population, 5.7% in Ireland. While I do not believe that simply meeting this arbitrary quota will necessarily produce radical change within poetry culture, it is, at the very least, a useful, basic benchmark for what representative inclusion might look like on a purely statistical level.

Of all seven magazines, only Poetry London and The Poetry Review meet this most basic figure. In this data set, only twenty articles were written by just twelve critics of colour. For comparison, 18 articles were written by white critics named David, and 39 articles were written by white women named Katherine. It’s worth noting, however, that women aren’t being adequately represented either.

The Guardian: until the past few weeks, in which Kate Kellaway reviewed Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky With Exit Wounds and Ben Wilkinson reviewed Daljit Nagra’s British Museum, The Guardian had not published a review of a poet of colour in four hundred and forty six days, when Sandeep Parmar reviewed Vahni Capildeo’s Forward Prize-winning Measures of Expatriation on February 19 2016. Incidentally, Parmar’s article was also the last time The Guardian published a review by a critic of colour, a run which is currently ongoing at four hundred and sixty-five days. It is also the first time The Guardian has reviewed a poet of colour who has not won a national prize since Kellaway covered Karen McCarthy Woolf’s An Aviary of Small Birds on November 23 2014. You’ll remember Woolf as the editor of Ten: The New Wave. For reference, the last time this happened for a white poet was two weeks ago, when Nicholas Lezard reviewed Bethany W Pope.

PN Review’s poor showing of just ten reviews of books by poets of colour is somewhat misleading. Of these ten, five were pamphlets covered in Alison Brackenbury’s round-up articles, in which each book is lucky to receive more than a few sentences of critical attention. Of the five full collections, only one was given its own solo review, Alex Wong’s Poems Without Irony, published by Carcanet, where PN Review editor Michael Schmidt works as Publisher. In two years’ worth of criticism – 138 articles totalling around 140,000 words, at a conservative estimate – PN Review dedicated roughly 2,500 words to poets of colour, about 1.5% of its review space.

The Poetry Review boasts some relatively positive statistics. A major factor in these unusually high numbers is Kayo Chingonyi. Chingonyi is a British-Zambian poet and critic who co-edited the Autumn 2016 issue of The Poetry Review, commissioning 2 of its seven total critics of colour, and 7 of its 23 reviews of poets of colour; in the following issue, Chingonyi himself reviewed two more poets of colour. Across the board, Chingonyi wrote or comissioned 30% of all articles by people of colour in the UK and Ireland in the past two years. This is an unreasonable burden to place on one individual.

Poetry London’s positive statistics are also a result of a temporary change in editorship. The Summer 2017 issue, published last week, was edited by Martha Kapos and Sam Buchan-Watts, and featured five reviews by critics of colour, and reviews of nine books by poets of colour; this single issue accounts for 38% of Poetry London‘s reviews by critics of colour in the past two years, and 36% of its reviews of poets of colour.

It’s also worth noting that the twelve critics of colour who did achieve publication are exceptionally qualified: these writers have a disproportionately high number of literary prizes, lectureships, editorships, academic and artistic residencies behind them for their career stage. Dzifa Benson’s background offers a small variation on this trend: her residencies at Tate Britain, Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and the Institute of Contemporary Arts were for performance theatre, not poetry. Again, she was commissioned by Kayo Chingonyi. It is an observable fact that white editors do not open doors for critics of colour unless they have already been institutionally verified several times over.

This is what I mean when I say just hitting quotas is not enough. A quota will not tell you when poets of colour are included as an afterthought or a token gesture. It will not ensure that the attention given to poets of colour is in any way a sustained, committed endeavour. If people of colour are not included at vital, decision-making positions, the systematic exclusion of people of colour in poetry criticism will not change, not least because white critics and editors are not sharing the burden of responsibility.

On gender, things are relatively encouraging. Aside from the PN Review and Poetry Ireland Review, most publications are approaching a basic level of gender parity, with Poetry Wales, Poetry Review and The Guardian leaning marginally in favour of female critics. All three are edited by women, and the Poetry Review‘s editorial practice has changed markedly since Emily Berry’s tenure began last year. In almost every case, however, female critics review more books per article than their male counterparts, and men disproportionately review other men.

As a poetry critic, being given space to review a single book is a chance to make a significant contribution to a critical conversation. These reviews are overwhelmingly commissioned to men, a total of 157 compared to just 72 by women across all platforms. Even more intriguingly, while women review male and female poets about equally (33 women to 34 men, with 5 anthologies), men almost exclusively review other men, by 128 to 22. Simply put, male critics and poets alike are routinely given more space and prestige than their female colleagues.

This is most starkly illustrated by Alison Brackenbury’s role as resident pamphlet reviewer at PN Review, where she accounts for ten of the thirty-five total articles by women and seventy of the one hundred books reviewed by a female critic. There is a gendered labour gap at work at the magazine which aptly matches its apathy towards poets of colour. PN Review is by white men, for white men.

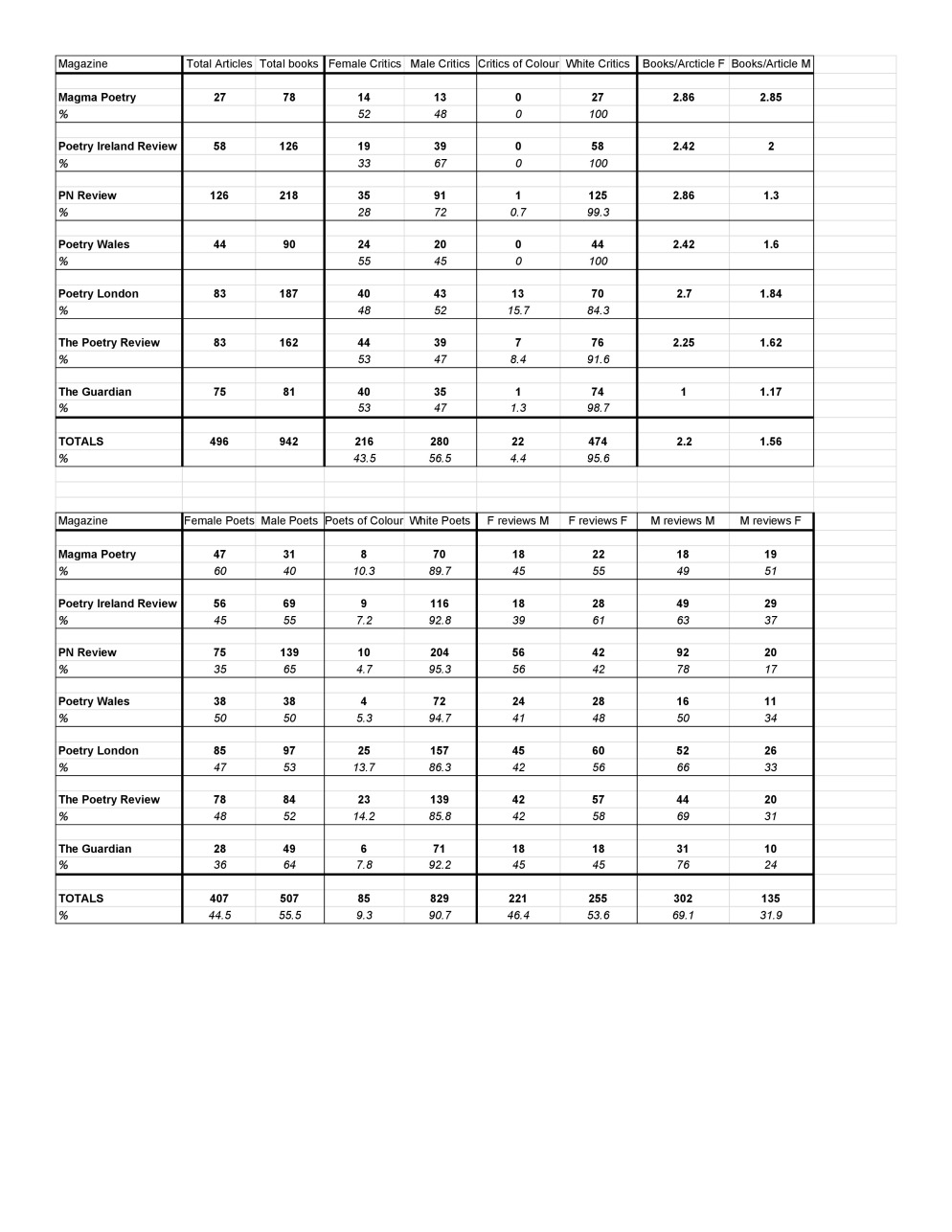

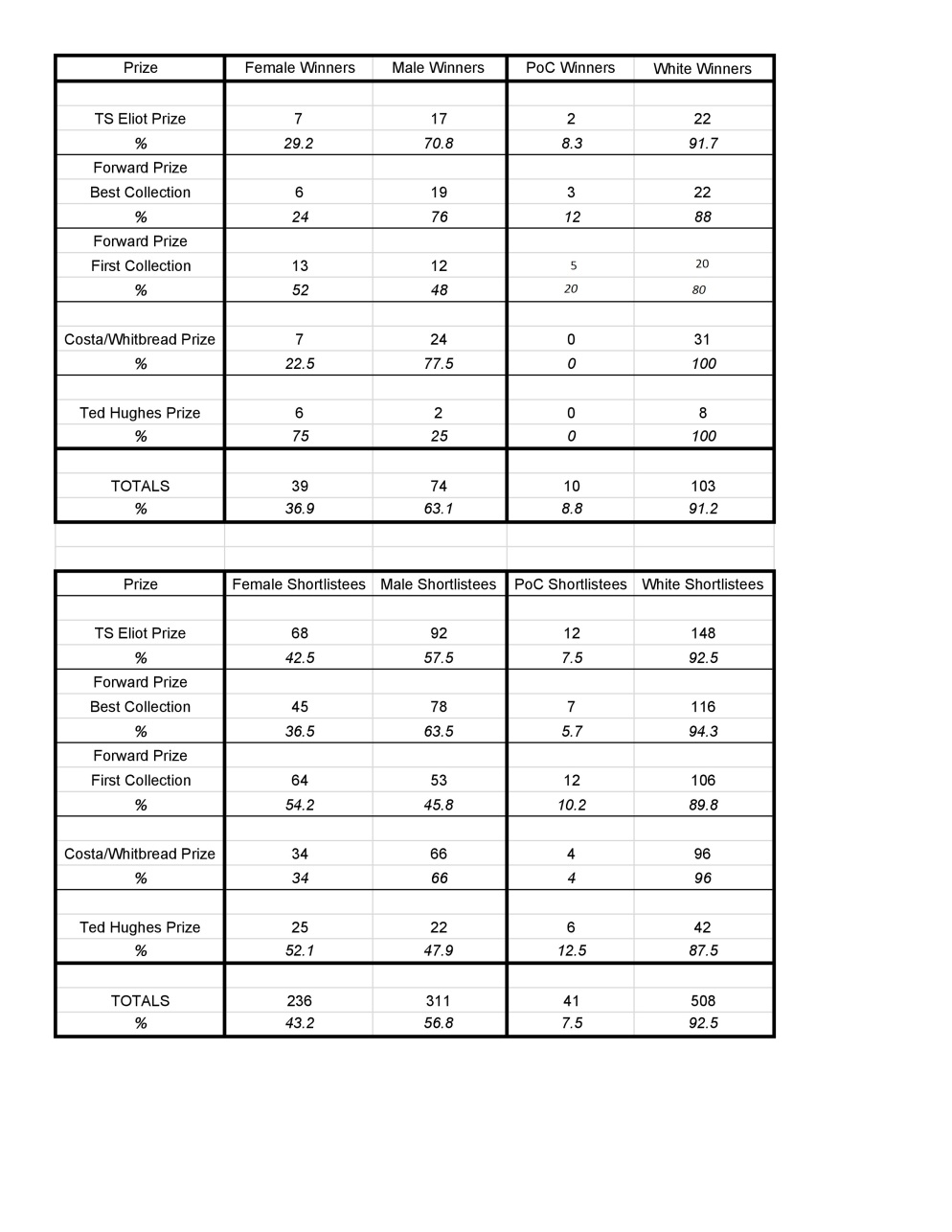

At the outset of this paper I mentioned how recent victories for poets of colour might be seen as a sign of positive change. It is, however, vital to put these results into historical context. I studied four major poetry prizes: The Forward Prize (established 1992); The TS Eliot Prize (established 1993); The Costa Prize (formerly the Whitbread Prize, which has been running a poetry award since 1985); and the Ted Hughes Prize (established 2009). To give an idea of the resources awarded by each: the TS Eliot awards £20,000 to its winner; The Forward Prize £10,000 for Best Collection and £5,000 for Best First Collection; the Costa Prize awards £5,000 with a possible £30,000 if the book also wins Book of the Year; the Ted Hughes Prize awards £5,000.

The questions this data set asked were also very simple: who is shortlisted for these prizes, and who wins them?

Only the newly created Ted Hughes Prize has awarded more women than men, by 6 to 2, and no poet of colour has ever won.

Between 1985 and 2000, the Costa Prize was won only once by a woman, Carol Ann Duffy in 1993. Jane Yeh was the first poet of colour whose work featured on the shortlist in 2005, its twenty-first year. In its thirty-one year history, no poet of colour has ever won the Costa Prize.

In its twenty-four years, the TS Eliot Prize has been won only twice by poets of colour, and only seven times by female poets. Its first eight winners were white men, and Derek Walcott was the first poet of colour to win, in the 18th year of the prize’s operation.

In a similar vein, only three of the first twenty Forward Prize winners were women, and only in 2014, its twenty-third year, was the prize awarded to a poet of colour, Kei Miller. The Forward Prize for Best First Collection is slightly different, in that Kwame Dawes won in 1994. Between 1995 and 2004, the First Collection Prize had all-white shortlists until Jane Yeh was shortlisted in 2005.

It may also be worth noting that of the ten poets of colour to have won one of these five prizes, only three self-define as British: Daljit Nagra, Mona Arshi and Sarah Howe, both of whom won their prizes in 2015.

Since 1985, thirty poets of colour have been shortlisted for awards a total of forty-one times, with ten wins. To put this into context, in the same time period six white male poets – namely, Simon Armitage, Seamus Heaney, Don Paterson, Sean O’Brien, Robin Robertson and David Harsent – account for fifty-three shortlistings and twenty-one wins. Poets of colour were also disproportionately awarded the Forward Best First Collection, twelve out of the total of forty-one shortlistings and five of ten wins.

If encouragement can be taken anywhere, it is in the fact that of these forty-one shortlistings, twenty-two of them came in the past four years; while that does indeed mean that in the twenty-seven years from 1985 to 2012 only nineteen poets of colour were shortlisted for anything, it does suggest things are changing. If we take data from only the years 2013-2016, the percentage of poets of colour shortlisted rises to 18.6, and a remarkable 30% of all winners; likewise, the gender proportion is flipped, with 54.2% of female shortlistees and 55% of winners.

The idea that poetry prizes might be awarded to women is a relatively new one; that people of colour might also be rewarded for their work is newer still, and it is too early to say whether these changes mark a meaningful departure from the dominance of white male poets. Without a concordant commitment to the hiring of critics of colour and the reviewing of poets of colour, these islands lack the diverse critical culture necessary to understand in complex or nuanced terms the work of poets of colour. I fear that after these few positive years we – white critics and scholars – may consider the job done and turn a blind eye to the 100% white editors commissioning 96% white critics to write about 91% white poets. Prizes are a proven, if limited, antidote: of the eighty-five books by poets of colour reviewed in the featured data set, twenty-one were by prizewinners; indeed in The Guardian’s case, this is all but the only guarantee of critical attention.

As Sandeep Parmar notes in her seminal essay ‘Not A British Subject: Race and Poetry in the UK’: ‘Mechanisms in place systematically reward poets of color who conform to particular modes of self-foreignizing, leaving the white voice of mainstream and avant-garde poetries in the United Kingdom intact and untroubled by the difficult responsibilities attached to both racism and nationalism.’ Kate Kellaway’s review of Ocean Vuong, for example, invokes troubling cultural and racial clichés and stereotypes by introducing the poet as ‘born on a rice farm’ in her first sentence, and indebted to a white male mentor, Ben Lerner, in her second. This impulse to deliberately other poets of colour is precisely why the dire lack of critics of colour is such an urgent issue.

Earlier I mentioned the backlash against poets of colour in the literary press; when white male poet Jacob Polley won the TS Eliot prize this year, not only was there a distinct lack of outrage, The Guardian reviewed his collection, featured ‘Every Creeping Thing’ as Poem of the Day, and commissioned him three times to talk about his life and work, with such softball questions as ‘One review described what Polley does as a calling, “a kind of secular transubstantiation”. Would he agree?’ Where poets of colour like Vuong and Sarah Howe have orientalising narratives imposed upon them, white poets are commissioned to write their own stories on national platforms.

The scholar Sara Ahmed notes in the conclusion of her book On Being Included: ‘When a category allows us to pass into the world, we might not notice that we inhabit that category. When we are stopped or held up by how we inhabit what we inhabit, then the terms of habitation are revealed to us.’ As white poets, critics and scholars, we must acknowledge how centralising and normalising whiteness makes our creative communities exclusive by design. We must demand not just token inclusion of poets and critics of colour but that they be given equal space, resources and agency to direct critical and creative discourses. In short, writers of colour should not be compelled to spend their careers talking about nothing but race.

The work of a poetry book is only partly within its covers; the conversation, argument or statement it proposes is maintained or denied by the attendant critical community. In malicious hands, a book may be mocked or dismissed or simply ignored if that book does not behave itself as the reader demands, if it does not reinforce a given critic’s prejudices. It doesn’t take much searching to find reviews that misread or misrepresent a book’s intentions, intentionally or otherwise, coercing it into a state of palatability, or silence.

Even a preliminary study of British and Irish poetry magazines and prizes shows how ingrained is the culture of structural racism and misogyny. I hope these figures may be useful, and that knowing the true nature of our community is the first step toward changing it. Thank you for reading.

PS: At the time of writing, the figures I am working from are in a somewhat scrappy form; I am working to make this project into a fully searchable database using Google spreadsheets; this process is turning up small discrepancies in the raw data (mostly regarding anthologies and pamphlets), and once I have complete statistics I will update this article. I also plan on keeping these facts regularly updated, and investigating up to five years’ worth of material for a clearer view of poetry criticism’s recent history in these islands, perhaps expanding the number of featured platforms.

If you enjoyed this and would like to help me keep doing it, please have a look at my Patreon. You can pledge as little as $1/month, every pledge is massively helpful. Thanks for reading.